New York is a running capital. From the loops of Central Park to the West Side Highway, mileage is ramping up. But as volume increases, so does the most common complaint we see in our clinic: Posterior Thigh Pain.

Many runners dismiss this as just “tight hamstrings” or a minor strain. They foam roll, stretch, and keep running. Then, at mile 18 of their long run, the muscle seizes up.

At Dr. Barber Clinic, we treat the elite and the recreational runner alike. We know that “posterior thigh pain” is rarely just a simple tight muscle. It is often a specific mechanical failure that requires a specific fix.

If you want to make it to the starting line healthy, you need to understand why your hamstring is failing. Here are the 5 evidence-based reasons your posterior thigh hurts, and why standard “RICE” (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) is outdated.

If your pain is located deep in the gluteal fold (right where your hamstring meets your “sits bone”) and gets worse when running uphill or sprinting, it is likely not a strain. It is High Hamstring Tendinopathy (HHT).

HHT is a compression issue. When you run, the tendon is compressed against the bone. Traditional stretching actually compresses the tendon further, cutting off blood supply and making the injury worse. This condition requires heavy isometric loading, not stretching.

The Science: A 2023 review in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy confirms that proximal hamstring tendinopathy requires progressive tendon loading protocols, and that passive stretching can delay recovery by increasing compressive loads on the tendon insertion.¹

Your hamstring acts as a brake. When you swing your leg forward, the hamstring contracts to slow the leg down before your foot hits the ground.

If you over-stride (landing with your foot too far in front of your body), you are forcing the hamstring to apply the brakes with the muscle fully stretched and under massive tension. This mechanical overload is the #1 cause of recurring strains. No amount of massage will fix a gait error; you must fix your cadence.

The Science: Research in Gait & Posture demonstrates that increasing running cadence (steps per minute) by just 5-10% significantly reduces the peak force on the hamstring and knee joints, lowering injury risk.²

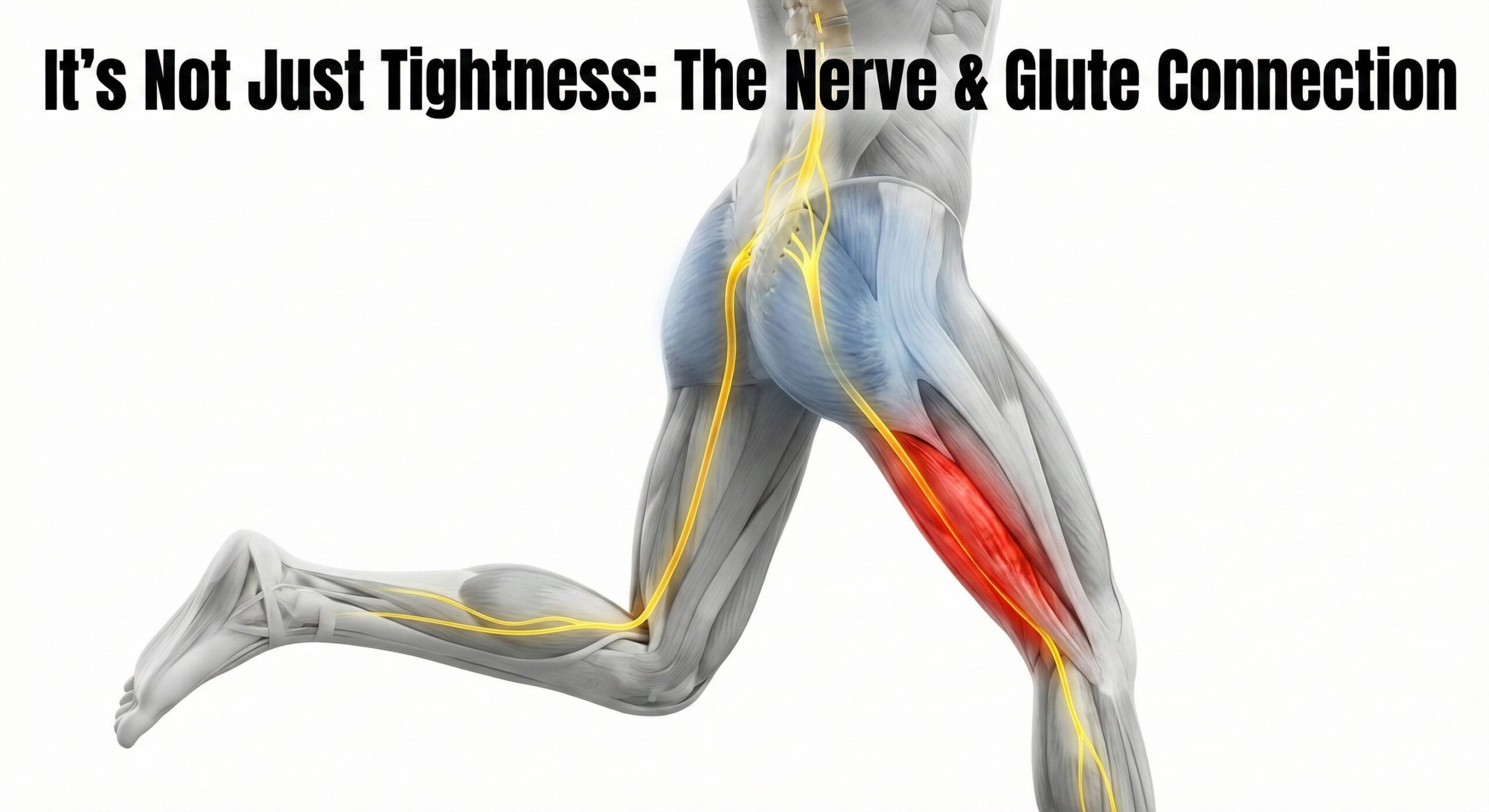

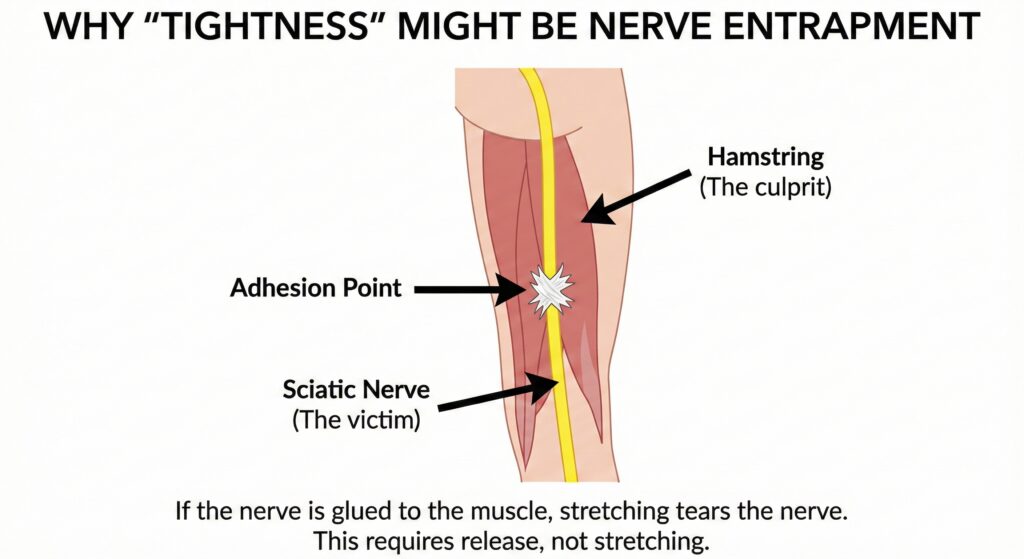

The sciatic nerve runs directly under the hamstring muscles. In runners, scar tissue from old injuries can “glue” the nerve to the muscle fascia.

When you run, the nerve should slide freely. If it’s stuck, every step tugs on the nerve, creating a sensation of “tightness” or a dull ache that never goes away, no matter how much you stretch. In fact, stretching often irritates the nerve further (neurotension).

The Science: A study on “Hamstring Syndrome” highlights that entrapment of the sciatic nerve can mimic chronic hamstring strains. Surgical or manual release of these adhesions is often required when conservative stretching fails.³

Running is a team sport for your muscles. The gluteus maximus is the primary mover (the Captain), and the hamstring is the assistant.

In many modern runners who sit at desks all day, the glutes become inactive (“Glute Amnesia”). The hamstrings are forced to take over the job of extending the hip. They aren’t designed for this workload, so they become overworked, hypertonic (tight), and eventually tear. You don’t need to stretch the hamstring; you need to wake up the glute.

Most runners lack eccentric strength—the ability of the muscle to be strong while lengthening.

Classic gym exercises like the Seated Leg Curl only train the concentric (shortening) phase. But running tears happen during the lengthening phase. If you aren’t doing Nordic Hamstring Curls or Romanian Deadlifts (RDLs), you aren’t preparing your tissue for the demands of the pavement.

The Science: A meta-analysis in the British Journal of Sports Medicine found that including the Nordic Hamstring Exercise in training protocols reduced hamstring injury rates by up to 51%.⁴

We don’t tell runners to “just stop running.” We find a way to keep you training safely by resetting the nervous system that controls the muscle.

Don’t let a “nagging ache” turn into a DNF (Did Not Finish).

Book an Appointment or Free Discovery Call